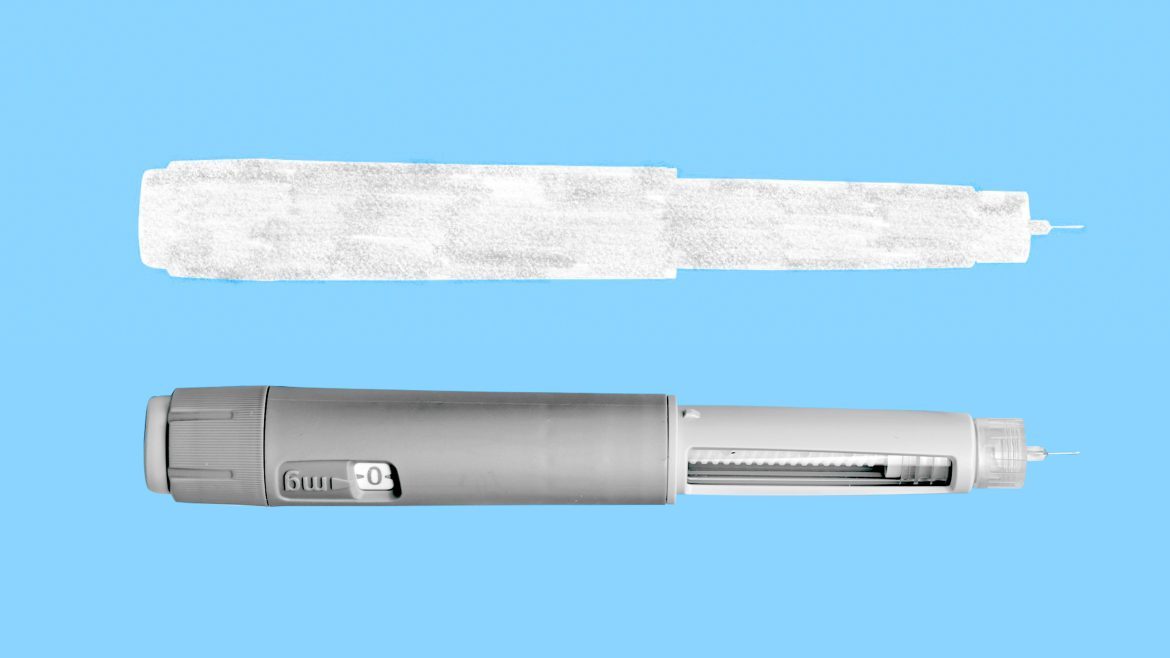

The wave of new obesity drugs has been defined as much by people who are taking them as by those who aren’t. For all the hype, the weekly shots have been awfully hard to get ahold of. Semaglutide, sold as Wegovy and Ozempic, and tirzepatide, a newer competitor branded as Mounjaro and Zepbound, first appeared on the FDA’s shortage list in 2022. They’ve been intermittently unavailable ever since. Shortages are a problem in part because these drugs must be taken consistently; if they aren’t, their dramatic weight-loss effects disappear. People have scrambled to make do—stretching out doses, turning to older obesity medications, and finding off-brand dupes of the drugs.

In the era of shortages, Ozempic copycats have become a billion-dollar cottage industry. Some are illegal fakes purchased from shady online sites, but not all. As long as the drugs are classified by the FDA as in shortage, entities called compounding pharmacies can make and sell versions that the agency says are “essentially copies.” Large telehealth platforms such as Hims & Hers and Ro now prescribe and sell compounded semaglutide; by one estimate, it constitutes up to 30 percent of the semaglutide sold in the United States.

But these versions can pose health risks. Compounded drugs are not as tightly regulated as brand-name ones. The FDA doesn’t verify whether they’re effective or safe, so people “have to beware,” Robin Feldman, a professor at UC Law San Francisco who specializes in pharmaceutical law, told me. Compounded and fake drugs alike can come with unknown substances, impurities, and unclear instructions that can lead to overdoses. The FDA recently warned that Americans have gotten very sick from overdosing on compounded semaglutide, noting that in some cases, people have inadvertently taken 20 times the required dose.

Novo Nordisk and Eli Lilly, the companies that manufacture semaglutide and tirzepatide, respectively, have repeatedly made assurances that they are working to ramp up production. Earlier this month, the drugmakers appeared to finally deliver on their promises. First, all forms of tirzepatide were listed as “available” on the FDA’s drug-shortage website—and then, a few days later, the same was true of all but one form of semaglutide. That still may not be enough to curtail the troubling rise of off-brand obesity drugs.

The basic problem is that, for many people, getting a prescription filled is still very much up to chance. Supply issues have improved for some, Ted Kyle, an obesity-policy consultant, told me, but others are having to wait more than two weeks to fill their prescriptions. Reliable information about the availability of the drugs is hard to come by. Instead, doctors and patients alike trade observations and hearsay about pharmacies that may have them in stock. Even the drugmakers themselves have acknowledged as much. The end of the shortage “does not mean that any pharmacy, or certainly every pharmacy, has all 12 dosage forms sitting on their shelves,” Eli Lilly’s CEO, David Ricks, said last week.

The mystifying linguistics of the FDA’s shortage policy is partly to blame for getting people’s hopes up. You might reasonably expect a drug listed as “available” to be, well, available—but that isn’t the case. As long as the drugs are on the list at all, they are still considered to be in shortage. Nearly all forms of semaglutide and tirzepatide are in this paradoxical scenario. They will be taken off the list only when certain criteria are met: Drugmakers must show, for example, that they have enough of a “safety stock,” an FDA spokesperson told me.

These technicalities matter because they open avenues for off-brand drugs to proliferate. Compounding pharmacies, to be clear, are a completely legitimate part of American health care. Their usual function is to make custom versions of a medication when a patient can’t take it in its original form. If, say, you can’t swallow a large pill, your doctor might have a compounding pharmacy make a liquid version of the drug. With all the interest and money in obesity drugs, their ability to legally make copies of drugs in times of shortage has created an off-brand-Ozempic bonanza. “Compounding has exploded as its own mini-industry,” Feldman said.

But in the rush to profit off the shortages, it isn’t always clear where compounding pharmacies source raw semaglutide and tirzepatide. They certainly aren’t sold by the drugmakers, and are likely made by independent labs or imported from China or India, Tim Mackey, a counterfeit-drug expert at UC San Diego, told me. In some instances, the drugs are made with non-pharmaceutical-grade ingredients or substances that are chemically related but different from the real active ingredient, such as semaglutide salt. With so many unknowns, “it’s impossible to control for quality and safety,” says Angela Fitch, the chief medical officer of Knownwell, a telehealth obesity platform that offers only brand-name obesity drugs. In some cases, what look to be compounded obesity drugs for sale online are actually just outright fakes manufactured by illegitimate pharmacies. Check that the pharmacy compounding your drug is licensed in your state, Scott Brunner, the CEO of the Alliance for Pharmacy Compounding, told me.

Drugmakers are doing everything they can to stop the dupes. Eli Lilly and Novo Nordisk are in a months-long litigation spree, suing companies that sell off-brand versions and counterfeit ones. They’re also spending many billions of dollars to further ramp up production to fully resolve the shortages, but there’s no telling when that will be. The FDA “cannot provide a general timeline” for when medications come off the drug-shortage list, the spokesperson said. Until that happens, drugmakers can’t do much. “I am skeptical that off-brand forms of these medicines will fade away anytime soon,” Kyle said. “Part of the reason that supply problems are easing is because these off-brand products are filling some of the gap.”

Yet after the shortages, these compounded drugs may persist. In a future when Ozempic is in abundant supply, people might still want the copycats. Part of the reason is that they are so much cheaper than the real thing: Hims & Hers offers compounded semaglutide at a starting rate of $199 a month—a sliver of the price of Wegovy, which can cost up to $1,350 a month. There might also be a legal argument for companies to continue making the off-brand versions. “There’s another path,” Feldman said. Compounding pharmacies that can show that their drug is different enough from an approved drug that it’s—again, the FDA’s words—“not essentially a copy” may do so even when there isn’t a shortage, she told me. Minor changes, such as switching out inert ingredients like fillers, won’t cut it, but adding an ingredient that plays a therapeutic role might, Feldman said. Some compounders already add vitamin B6 or B12 with the intent of alleviating nausea associated with GLP-1 drugs. If compounders can successfully make that argument, they “might have a decent case,” Feldman said.

Some companies are already planning for that future. When the shortage is over, Hims & Hers intends to customize obesity drugs to each customer, coupling them with supplements or other medications “to offset the side effects,” Andrew Dudum, the company’s CEO, told me. (The company recently disclosed plans to buy a compounding pharmacy.) Hims & Hers would not be “breaking the rules,” he said.

But those rules are still open to interpretation. “It appears some entities are trying to invent a new, unregulated way to mass-produce unapproved drugs by adding another ingredient or changing a dose,” a spokesperson for Eli Lilly told me. “That’s not how our system works.” Indeed, you could argue that vitamin B6 or B12 could be taken separately and still have the same effect, which would negate the need for the compounded drug, but that is not legally certain. Medications can be compounded for a patient as long as an “FDA-approved drug is not medically appropriate to treat them,” the agency spokesperson said. That there are so many ways to interpret that statement could no doubt be the basis for future lawsuits—and perhaps more copycat drugs. In addition to new obesity medications, Hims & Hers is already planning to compound drugs for testosterone replacement and menopause.

Shortage or not, off-brand obesity drugs may persist for the same reason generic drugs are so important: When people can’t find—or can’t afford—medications, they seek out alternatives. Off-brand drugs “are endemic in our supply chain because of consumers not having access,” Mackey, of UCSD, said. Unfortunately, people can be so desperate for access that they’ll gamble with their money and health to get it—especially when it comes to weight loss. Since the dawn of diet culture, people have fallen for all sorts of snake oil that can be ineffective or downright dangerous. What Ozempic and its kin offer is the potential to leave all of that behind. But a world in which millions of Americans keep taking risky off-brand drugs is not much of a step forward at all.